Contents

Intro/Inspo

To demonstrate the advantages of service-based architecture and cloud services in general - I took on a venture to modify an existing project into a cloud-ready project. In general, being cloud-ready means that the project is not based upon a single point of failure or monolithic service, instead, it breaks up as much as possible into smaller services. This provides advantages for performance being able to scale up the amount of services and being able to load balance across multiple servers. There are many more advantages, but that's something I'd have to focus on in an upcoming wrap-up for my migration to Kubernetes.

SmartCityTracker

The perfect contender for this project would have to be something unique, interesting, and cloud-applicable. Originally, my goal was to use one of the previous senior design projects at CMU - however, it seems that none of them utilized GitHub so this was not possible...

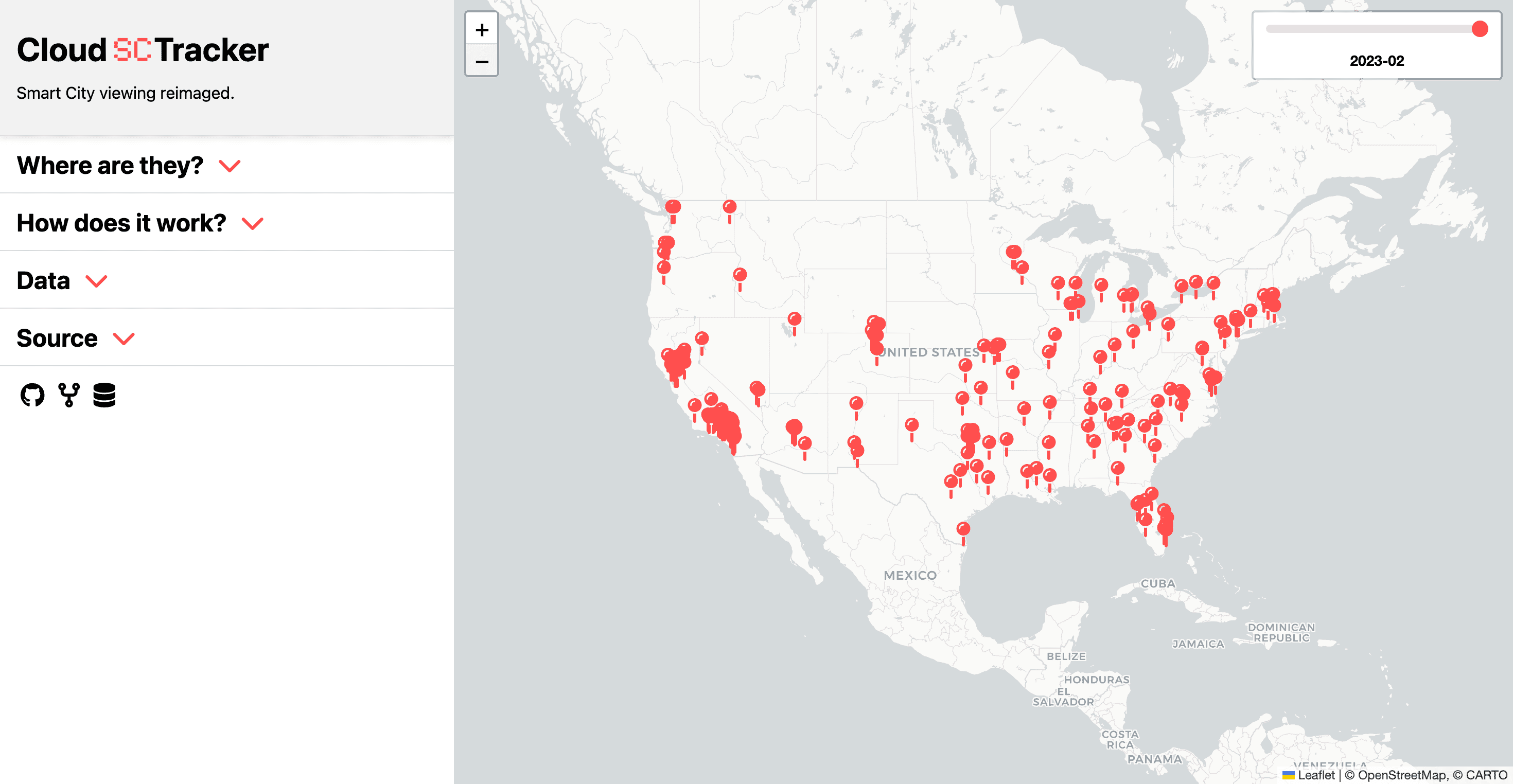

In my search, I found SmartCityTracker, a database of smart city innovations that was scraped from Google and compiled into a viewable database. This project consisted of a Zenodo database with all of the information and a web UI to display it.

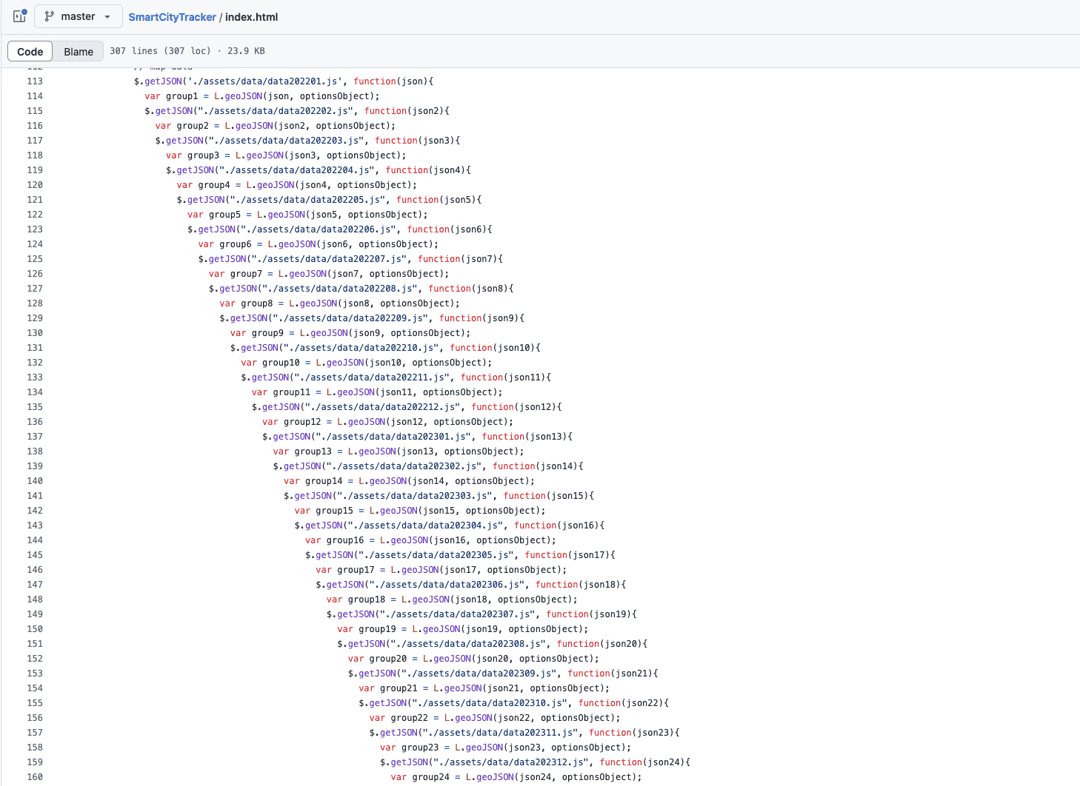

The problem? The information displayed was downloaded from Zenodo as a JSON in a javascript file and uploaded manually into the index.html of the project. When you visit the site, all of this was loaded, despite only a fraction of it being displayed.

This means that every time the database is updated, the HTML root has to be uploaded, leading to things like gigantic nested loops of HTML.

Disaggregating

To keep things fairly simple, the breakdown here would be to separate the frontend from the backend and the data from static assets.

Frontend

The new service for the frontend simply serves static HTML when you visit the page which has been modified with API calls to load data when it is accessed - instead of all at once. When data is requested from the new API, it pulls it from Firestore, leaving it to be completely dynamic.

Implementation

The first step for breaking up the datalink was to rip out all of the old. This meant the giant nesting would have to go, as well as most of the outdated Leaflet libraries - which restricted the kind of loading that could happen - or would have at least required me to find some outdated docs to do it.

The map works by displaying a layer of the Smart City data, in this case, it's a month and it's an entire JSON. To navigate the data, there is a slider, which corresponds to the month you are viewing.

This complicates things a little as the slider requires all of the timestamps to be known for it to populate. Previously this was done by loading all of the layers at once into the slider, requiring all of the data. Breaking this up would be a little more complicated since it would have to be loaded with unknown data. Fortunately, Leaflet allows this to be done by just creating the input range (vanilla HTML) with the number of timestamps - which can be gotten with a Firestore query.

const snapshot = await db.collection("data").get();

const files = snapshot.docs.map((doc) => doc.id);

And then fetched and passed through to the slider...

sliderElement.type = "range";

sliderElement.min = 0;

sliderElement.max = timestamps.length - 1;

sliderElement.value = timestamps.length - 1;

sliderElement.step = 1;

Boom. Too much time was wasted trying to figure out how to do this with a Leaflet slider when the answer was so much more obvious. But, there was still the second half of this, dynamically loading the data into the layers using a GeoJSON? I still have no idea what that is - but that's the fun part.

Originally, this was done by loading all layers at once. And you cannot just add layers dynamically, instead as it turns out you can delete the current map layer and display a new one - which works just as seamlessly.

if (currentGeoJSONLayer) {

map.removeLayer(currentGeoJSONLayer);

}

// Add new GeoJSON layer

currentGeoJSONLayer = L.geoJSON(data, {

// Add icon

pointToLayer: function (feature, latlng) {

return L.marker(latlng, { icon: customIcon });

},

// Add popup

onEachFeature: function (feature, layer) {

layer.bindPopup(`

<h3>${feature.properties.title}</h3>

<p>${feature.properties.description}</p>

<a href="${feature.properties.link}" target="_blank">Read more</a>

`);

},

}).addTo(map);

This solved some pretty major problems and made it easily off to the races. However, by far this was the biggest obstacle.

Closing thoughts

In a perfect world, the API could be separated into another service, but there simply is not enough traffic to justify this and the dataset is pretty lightweight as it is. However, if it came down to it, separately the two would allow for much easier scaling of the data. And if it came down to it, Firestore can directly be accessed by clients, eliminating the need for an API.

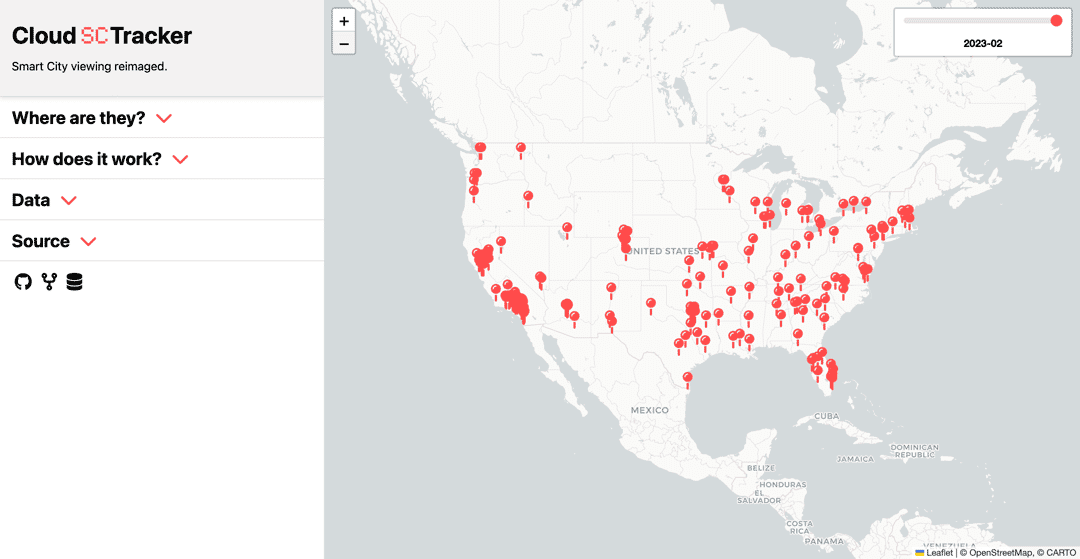

In a similarly perfect world, I would not have rewritten the entire project including the HTML and CSS, but here we are. Welcome to the fully redesigned Cloud SmartCityTracker!

Backend

With the data no longer being manually imported, it would have to be pulled through other means - directly from Zenodo. This fixes an entire step in the update pipeline and would make the project pull from a single source of truth instead of relying on multiple updates.

Pulling from Zenodo

Zenodo is kind enough to offer a developer API, which allows for downloading files from projects - and even without API access.

This meant that pulling the database would be as simple as...

const response = await axios.get(zenodoURL);

But the data is zipped which adds a fun extra step of unzipping. It was at this moment I also realized that Zenodo was not being used as a data source, instead it was shipped with the web UI. So on top of unzipping, the /assets/data directory would have to be pulled.

await new Promise((resolve, reject) => {

fs.createReadStream(zipPath)

.pipe(unzipper.Parse())

.on("entry", (entry) => {

if (entry.path.includes("/data/") && entry.type === "File") {

// Copy to extraction dir

const extractPath = path.join(extractDir, path.basename(entry.path));

entry.pipe(fs.createWriteStream(extractPath));

console.log(`Extracted ${entry.path}`);

} else {

// Skip

entry.autodrain();

}

})

.on("close", resolve)

.on("error", reject);

});

With the datafiles located, it was time to upload to Firebase.

await db.collection("data").doc(documentKey).set(jsonData);

And just like that, the data upload pipeline had been finished.

Sike

So as it turns out, the Github was the golden source of truth in this project and Zenodo has not been updated since 2023. Anyway, I'm still going to pull from Zenodo and pretend like this is the most recent data.

Firestore

This part is not as exciting and was actually quite boring. Basically, you just create a GCP Project to organize the environment, create a Firestore NoSQL database, create a service worker, add Database User to the service worker, generate an auth token, install the Node.js SDK, and you are off to the races.

Conclusion

All in all, this project turned out to be pretty interesting. I love throwing myself into projects that I know absolutely nothing about and having to learn a ton of new information. In this case, I learned what a smart city was, how to interact with Firebase, and how to use Leaflet.

I also reinforced my ego on web design. But that's not as important.

Technologies

- Docker

- Node.js

- ExpressJS

- Axios

- GCP/Firebase/Firestore

- Zenodo