Links

Check out the source code on Github

Contents

Intro

Finding an idea to work on for a thesis project is quite difficult. It turns out that it's something you spend a lot of time working on and even more time researching. Finding something that is intriguing but satisfies the broader goal is even more complicated. But then it hit me, I could be like Bill Harding from Twister and predict tornados, but use Machine Learning instead of a magical power.

Plan

Just like any great project, it starts with realizing that MIT did it first (and probably better).

Training machine learning models is all about having a quality dataset. Originally, I had been poking around NOAA's NSSL radar archives, but these are pretty intense. There are a lot of hoops to go through when downloading data and the amount of data they present is in much broader areas and is not labeled.

MIT made this a nonissue with the TorNet dataset, which compiles radar images into a nice, easy-to-train dataset that has already been labeled.

Implementation

While MIT had trained demo models on this dataset, they were limited by the size of their models, such as using a 2-D Convoluted Network by dropping the timeline.

Adding back this data timeline, we were able to make this into a 3-D model, which transforms this into temporal data and has the opportunity to greatly increase the model's performance.

Procurement

MIT hosts this dataset on Zenodo across multiple archives (2013). However, Zenodo is pretty slow for downloading, and planning for the future I decided to try and store this somewhere a bit faster.

The first step was to download it locally with Aria2c, which took about 6 hours, and then upload it to Backblaze S3.

def upload_files(file_list):

"""

Upload files to Backblaze B2 using the b2 CLI.

"""

for file in file_list:

command = ["./venv/bin/b2", "file", "upload", BUCKET, file, file]

try:

logging.info(f"Uploading '{file}' to B2...")

subprocess.run(command, check=True)

logging.info(f"File '{file}' uploaded successfully.")

except Exception as e:

logging.error(f"Failed to upload '{file}': {e}")

exit(1)

This was made pretty easy thanks to Backblaze's Python SDK.

In the future to inhibit egress fees and better load across the world (important for later) it was put behind Cloudflare through a generic CNAME proxied record. For this, you simply add the Backblaze endpoint (f000.backblazeb2.com) as the content and then when you access it, it ends up being

https://

proxy/file/bucket/file_name

Processing

With the amount of files in TorNet, over 200,000, it just crashes the Python kernel on loading with Keras. To avoid this, the records are parsed with TensorFlow and serialized into a TensorFlowRecord (TFRecord) that can then be fed into the model.

Without including too much code,

with tf.io.TFRecordWriter(output_path) as writer:

for file in tqdm(files, desc=f"Processing year {year}"):

features, label = parse_nc_file(file)

if features is not None:

example = serialize_example(features, label)

writer.write(example)

local_label_counts[label] += 1 # Update local counts

print(f"Completed {year}: {len(files)} files")

return local_label_counts

The TFRecord can be called through a writer object which can write serialized data. Since this works through the TensorFlow data pipeline, it also scales across CPU cores making it a pretty efficient way to parse data. Notable, it does create very large records even with smaller data types that essentially double the on-device storage requirements.

In this processing step, other things such as counting weight values, normalizing values, and removing NaN/flagging values occur.

Multi GPU

Before training, it was also important to take advantage of multiple GPUs - since that's generally more cost-effective for training. TensorFlow provides a default strategy for this, again making it quite easy.

strategy = tf.distribute.MirroredStrategy()

Parsing for Model

With TFRecords created, they then have to be loaded back in and prefetched for the model.

parsed_example = tf.io.parse_single_example(example, feature_description)

Normally, data would have to be split here for training, but TorNet already had the dataset split - so they were loaded as two "separate" datasets.

Model Definition

With the large amount of data, and crazy class imbalance (189267 Non-Tornados to 13857 Tornados), I added a lot of complexities to sort of boost the abilities of training.

Batch Normalization: to try and aid in faster convergence and retain stable training.Leaky ReLU: add additional activations to avoid dying neurons and enhance gradient flow.Spatial Dropout: prevent overfitting by dropping feature maps randomlyL2 Regularization: add weight penalties to prevent overfittingClass Weights: use the exact class amounts to avoid imbalance in training

And of course, this is all done on a sequential 3-D CNN which had 6 3DConv layers and a final Sigmoid dense layer for binary classification.

All in, this ended up with about 886,337 parameters, which is not too many.

Training

With about 200,000 images and a batch size of 8, that led to about 25,000 steps. As predicted, the training time with this model on TorNet was abysmal. On an RTX4060 locally, it was taking about 2 minutes per step. Multiple that by 25,000 - and yeah, that was not happening.

Moving to cloud GPU provider, Vast.ai, I could then take advantage of bigger and faster GPUs, such as an NVIDIA LS40. Which dropped step time to 10 seconds, and epoch time to almost 3 days - which was still not going to happen.

Finally, optimizing with multiGPU TensorFlow strategies, I landed on using 4 NVIDIA RTX4090s, which provided much better value for VRAM and TeraFlops, at about $1.6 an hour. With this instance, it was training at about 157 ms per step, or about 30 minutes to an hour per Epoch.

With Multiple GPUs, the batch was effectively multiplied by the amount of GPUs, so about 32. Meaning it required many less steps as well as training at less time per step.

With a high training time, and a risk of the kernel still crashing, checkpoints were utilized to a directory that was synced to Backblaze.

To ensure that only positive training would happen and stop the training as soon as it finished, EarlyStopping was added - and configured to default to the best weight.

Results

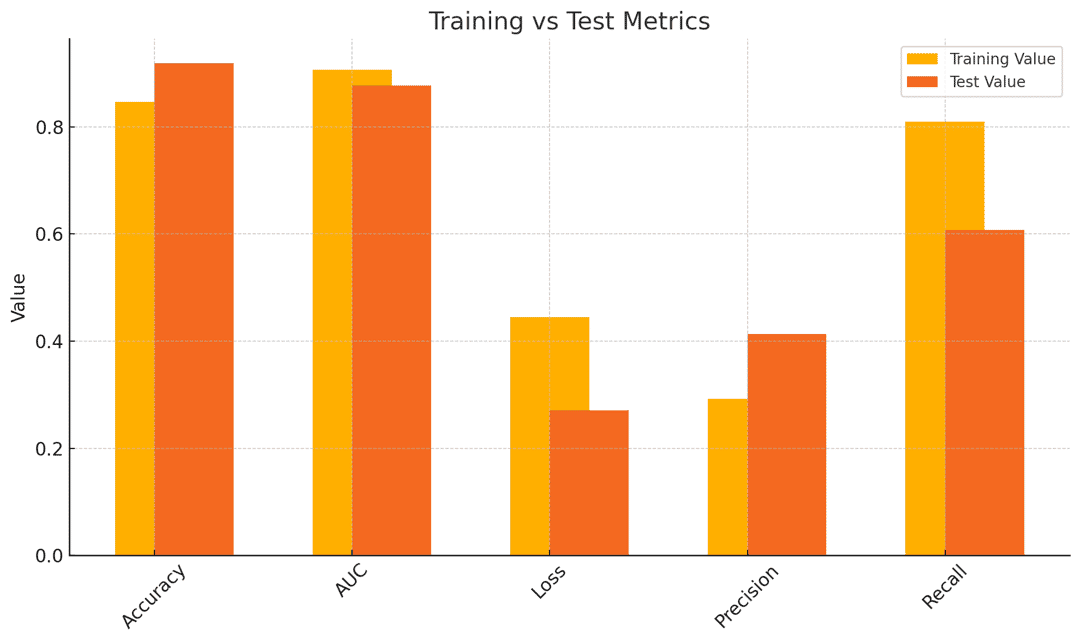

In the end, the model performed okay - and even an improvement over other models that had been trained, such as MIT's 2-D CNN.

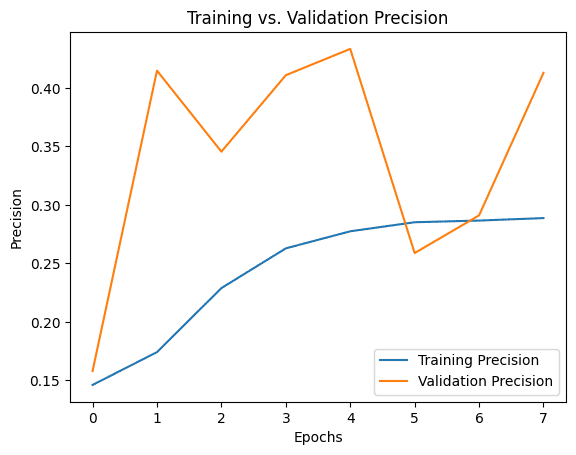

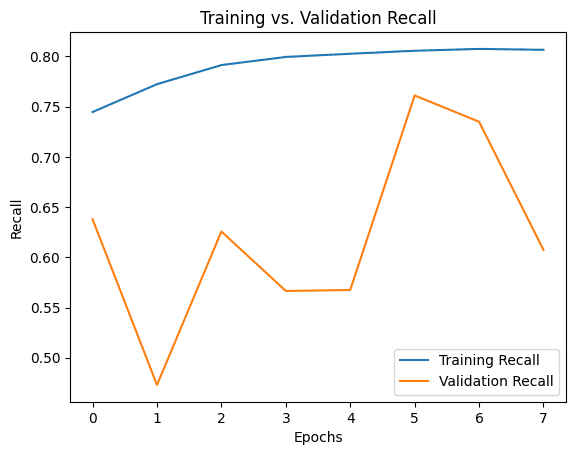

Looking at Precision and Recall over time, it's clear the model was not fully converging, and it struggled to lock down on predictions.

Discussion

In the future, I believe that the model could improve based on more context - which would help it converge better. For example, providing additional data from NOAA such as area weather information or Satellite imagery - in a combined model.

This also provided a lot of insight into training as Vast's prices were not too bad, and are something I would use to aid in training time in other projects. Also as it turns out, it's nearly impossible to even get a GPU from other providers such as Oracle or Vultr, as they make you jump through tons of loops.